Projects

Labanotation for Writing

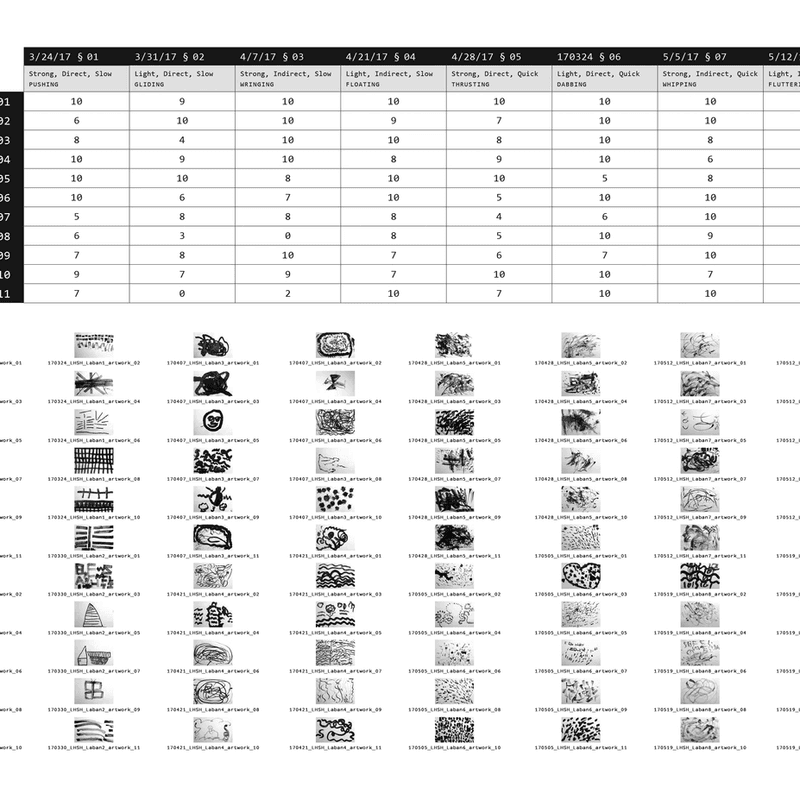

This project is an ongoing research experiment, started while running two workshops with first grade students in two different elementary schools; one in Texas in 2017, and one in upstate New York in 2019.

The workshop entails eight 1-hour sessions scheduled during after school programs. Research is conducted with one first grade group for “writing treatment” but really, I do it primarily for my understanding of the central role of writing and cursive in literacy and education at large.

It is what I call a “proto-writing” project based on the Laban Movement Analysis framework, which I discovered and stuck with me after meeting Professor Ewan Clayton, master calligrapher and calligraphy historian, in 2011.

The “Labanotation” or Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) provides a comprehensive vocabulary and analytic framework for the description of human movement, a standardized system for analyzing and recording any human motion, in this case writing strokes. Using LMA, one can systematically look at a unit or phrase of stroke movement in terms of the four major movement components of Body, Effort, Shape, and Space. These basic components can be identified and examined alone and in relationship to each other.

Also called “Kinetography,” LMA is a notation system derived from the work of Rudolf von Laban (1879–1958). Laban (1928) described his notation system in Schrifttanz (“Written Dance”) as a timeless example of patience, logic and meticulous accuracy. Laban’s initial work has been further developed by American movement and dance researcher Ann Hutchinson Guest (co-founder of the Dance Notation Bureau, New York, 1940) among others, and is used as a type of notation in other applications encompassing human movement analysis, robotics and movement simulation. One of my graduate students, Da Vontae Heath designed a booklet explaining the notation.

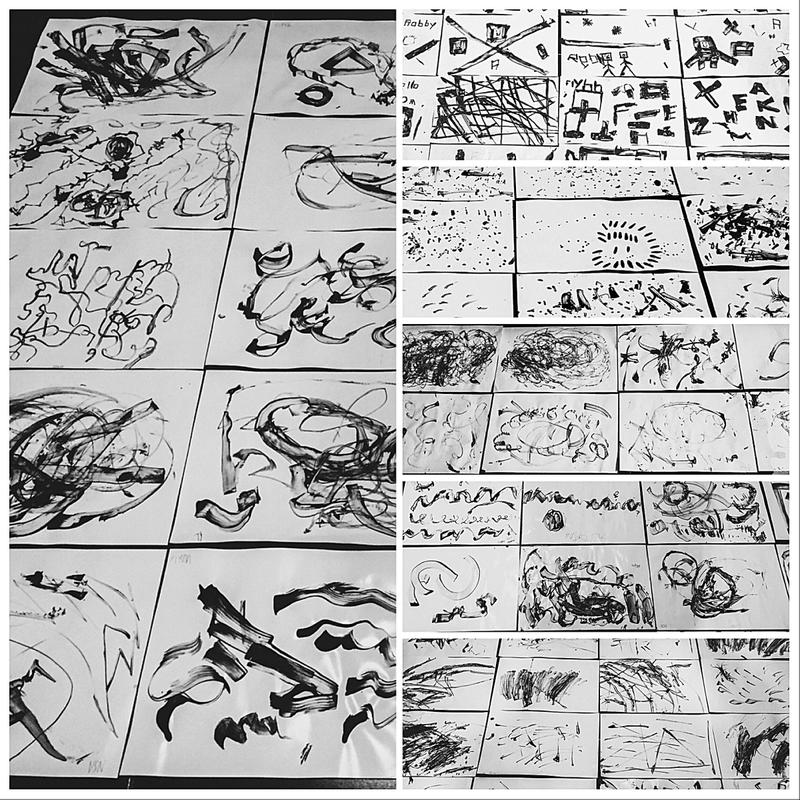

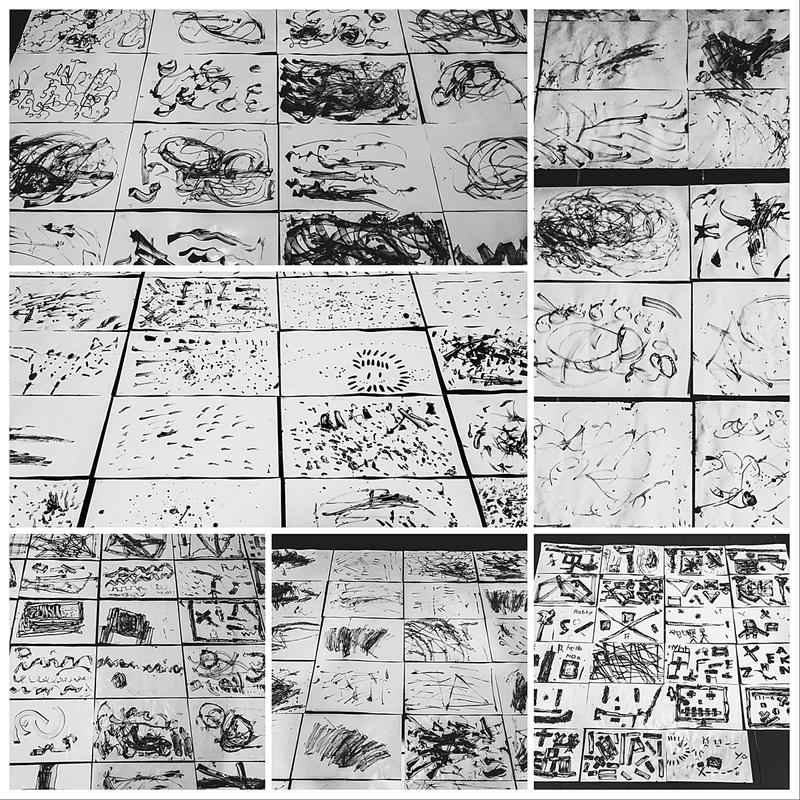

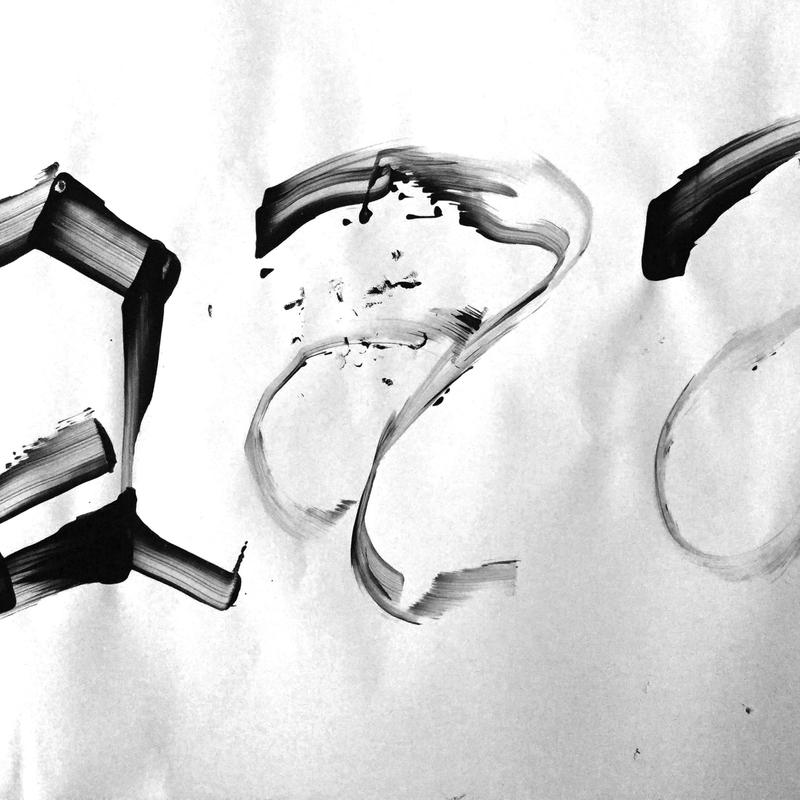

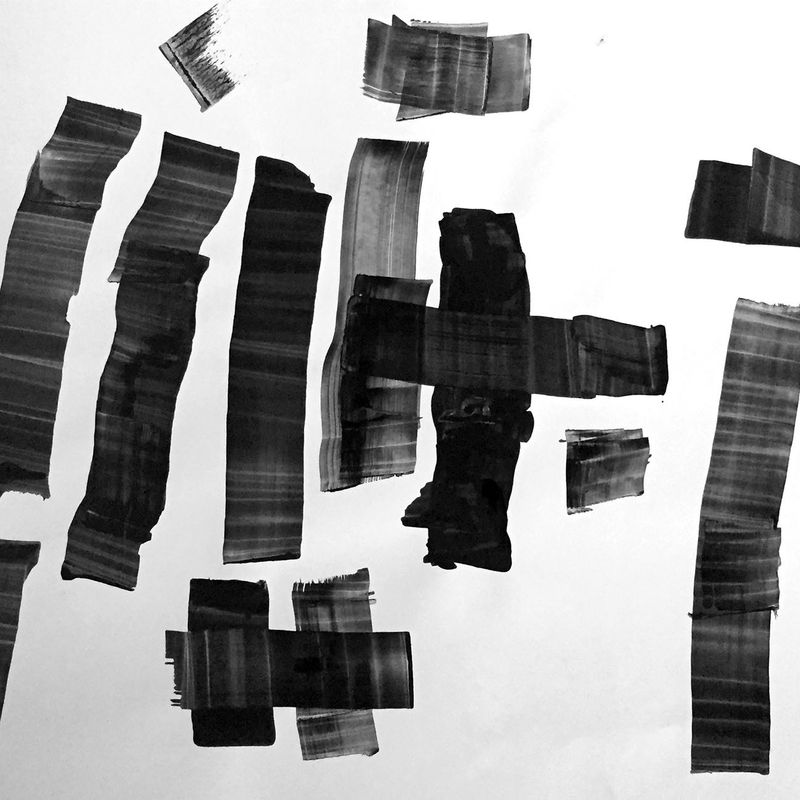

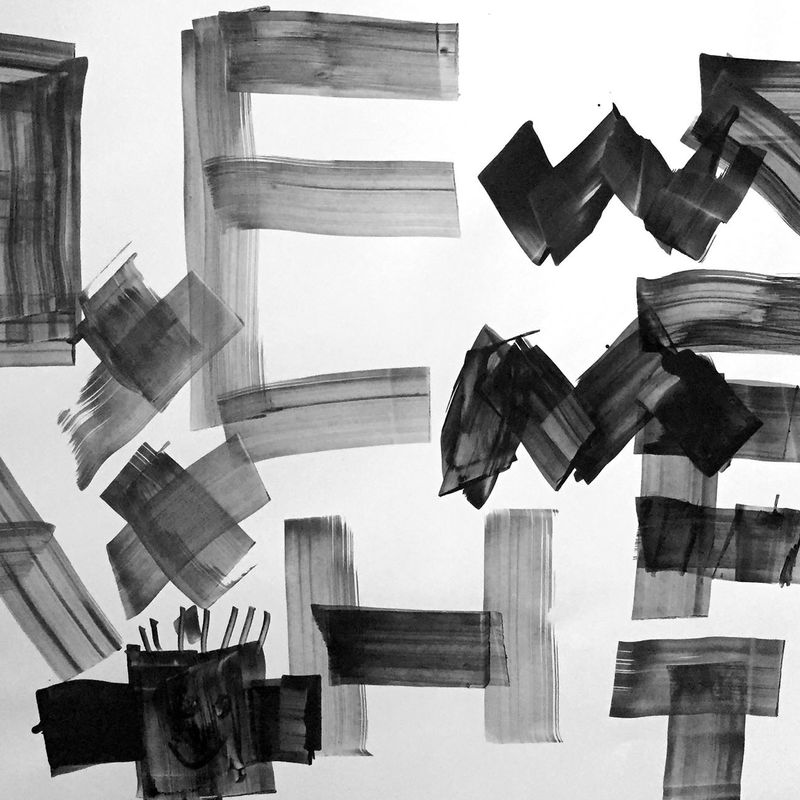

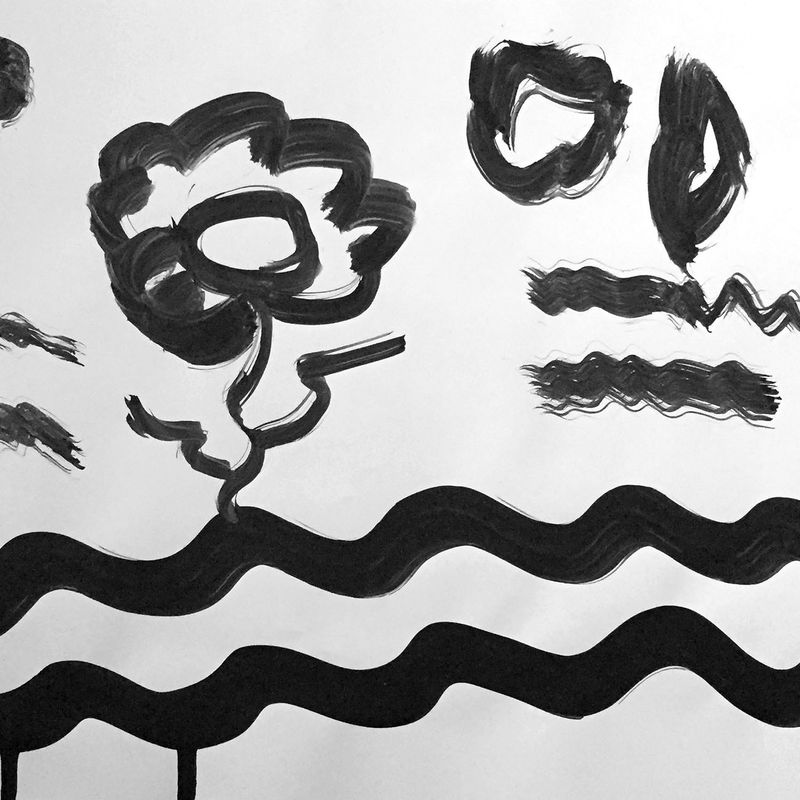

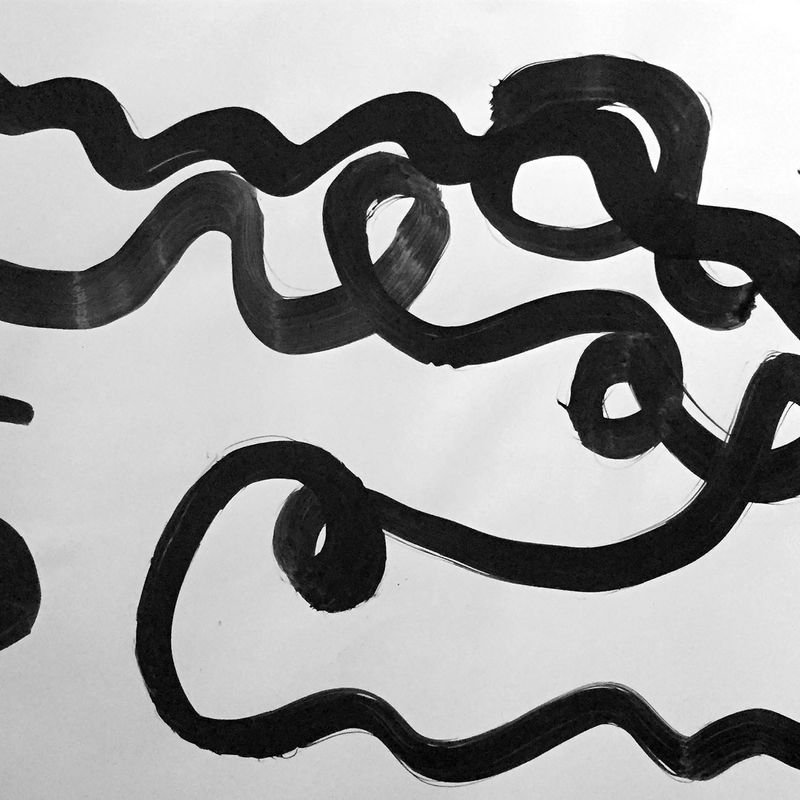

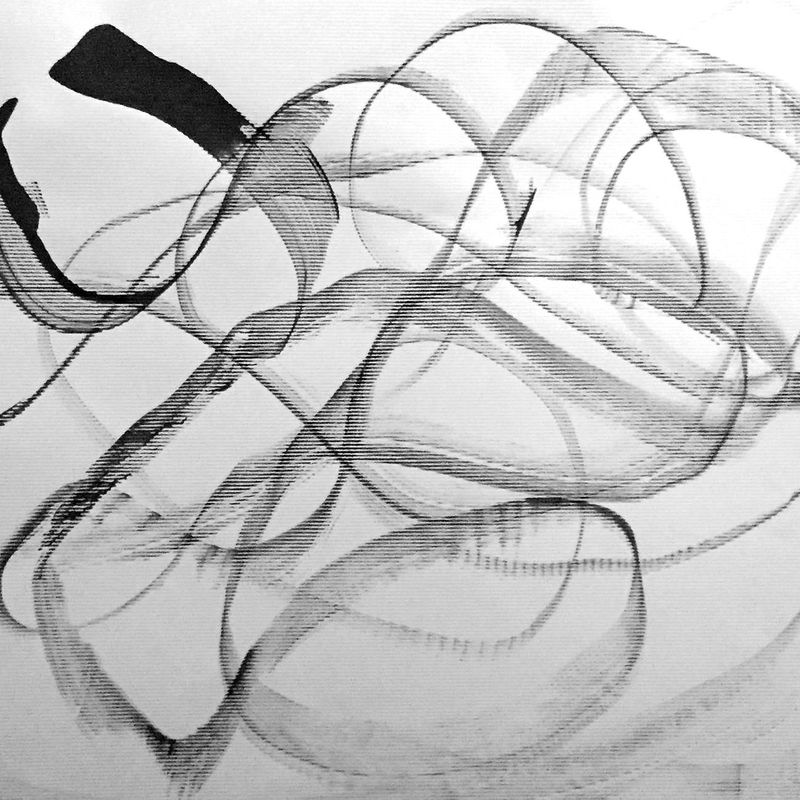

Workshops are 8-week long, and usually I have students to practice only one movement per session. The prompt is rather simple, and explained in quick demonstrations at the beginning, as well as with linguistic metaphors — words that render the concept of the energy under inspection, e.g. “twisting” for strong, indirect, and slow movements. There’s quite a bit of “backstage” and some kids do come up with interesting observations.

Immediately, the prompt informs the students that the “mark making” activity is a sort of performance to be explored — kinetic decisions that are rather different from those necessary to call letters via a keyboard. The exercise is indeed in the realm of writing, not drawing or setting prefabricated characters (type).

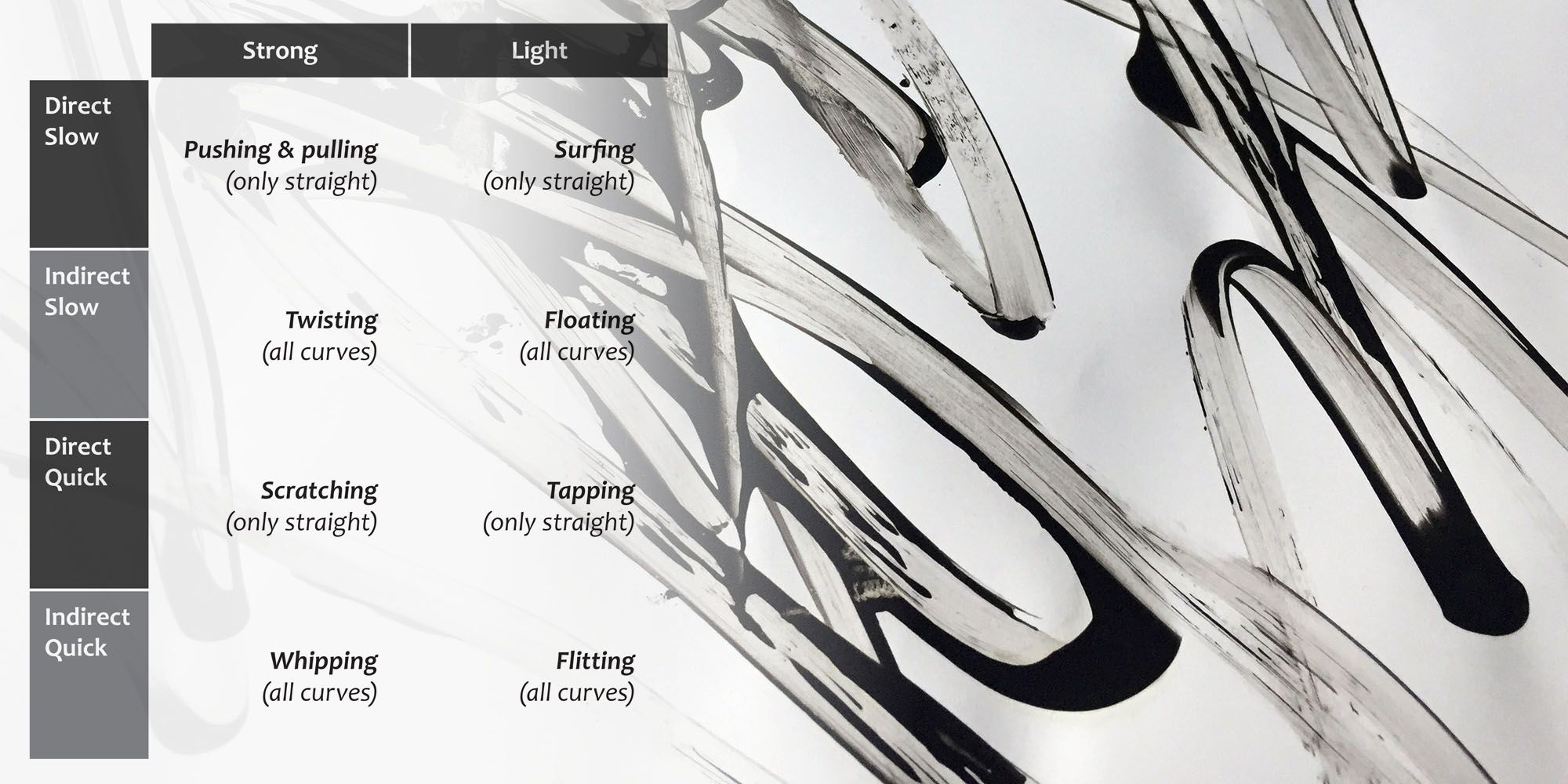

Here is an overview of the movements or framework:

1. Strong, Direct and Slow — Pushing

2. Light, Direct and Slow — Surfing

3. Strong, Indirect and Slow — Twisting

4. Light, Indirect and Slow — Floating

5. Strong, Direct and Quick — Scratching

6. Light, Direct and Quick — Tapping

7. Strong, Indirect and Quick — Whipping

8. Light, Indirect and Quick — Flitting

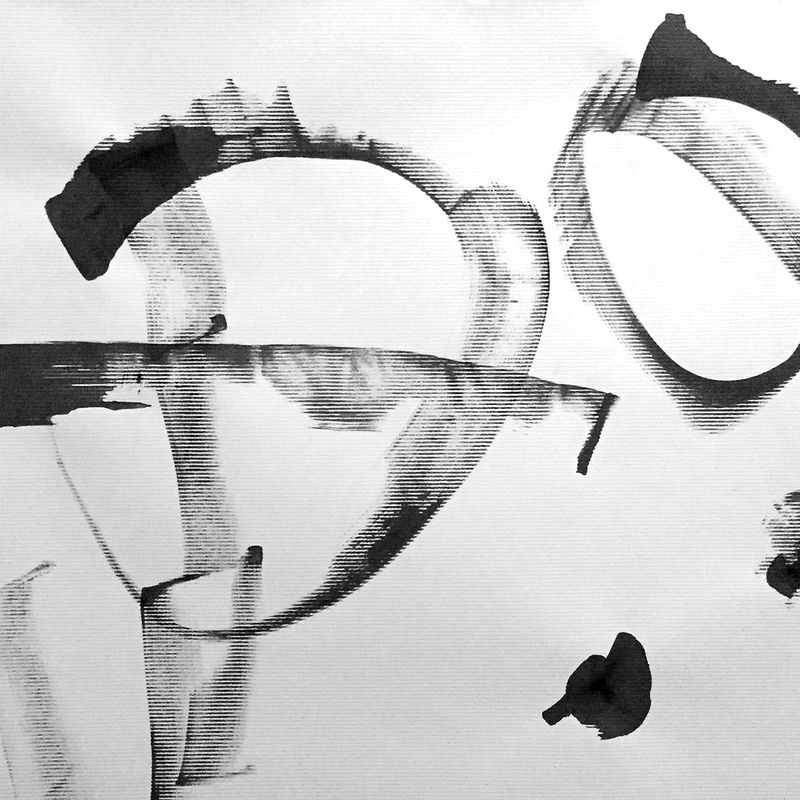

The tool is of paramount importance, and so, for ease of assessment as well, students in all sessions use a 1" (2.5cm) wide balsa stick. Long sticks of balsa are prepared in advance, cut in 6" (15cm) long pieces, and carefully sanded on the edges to have square corners. This part influences both the texture and the amount of translation contrast possible.

For most if not for all students, this workshop is the first time they get to use a broad pen — a major departure from the default ballpoint, radically different both in terms of grip and graphic mark. The ink is black tempera, lightly diluted.

The movements in the second half of the framework (5 to 8) are more closely related to what cursive writing is. That is when the research comes in — as a quest almost — to prove that cursive strokes are just more natural and easier to execute than those needed for a print “formata” hand. Interrupted writing or non-cursive has just too many phantom strokes (movements in the air that leave no mark on paper).

This study seeks to determine if children immersed in writing movement analysis will demonstrate greater interest in making marks or writing strokes as a tool for thinking.

It simply makes far more sense to have young learners practice cursive, to connect & form their ideas…, to write faster, and have the time and brain processing power to actually understand the content of what they write.

Non-cursive writing does not allow time for thinking about what is being written. Cursive supports selective attention, thought, observation, curiosity about and identification of text shapes. The kinesthetic activity of cursive writing supports engagement, attention and memory. Existing research linking LMA to the experience of learning to write (and to read), specifically with students of elementary school age, is not available.

Because the nature of literacy in a culture is repeatedly redefined as the result of technological changes, a question should be asked: why is typography not being taught in elementary/middle schools?

Writing movement does inform the letters we make and movement itself can be shown within the electronic media that we use for reading and writing. The challenge this poses is how to reconnect with the gestural roots of letterforms, hence the theoretical frameworks by Rudolf von Laban.

I believe this is of major service to society — a society that identifies literacy as a social good — to raise critical thinker-citizens, therefore important for the present and the future of our youth, for our civilization.

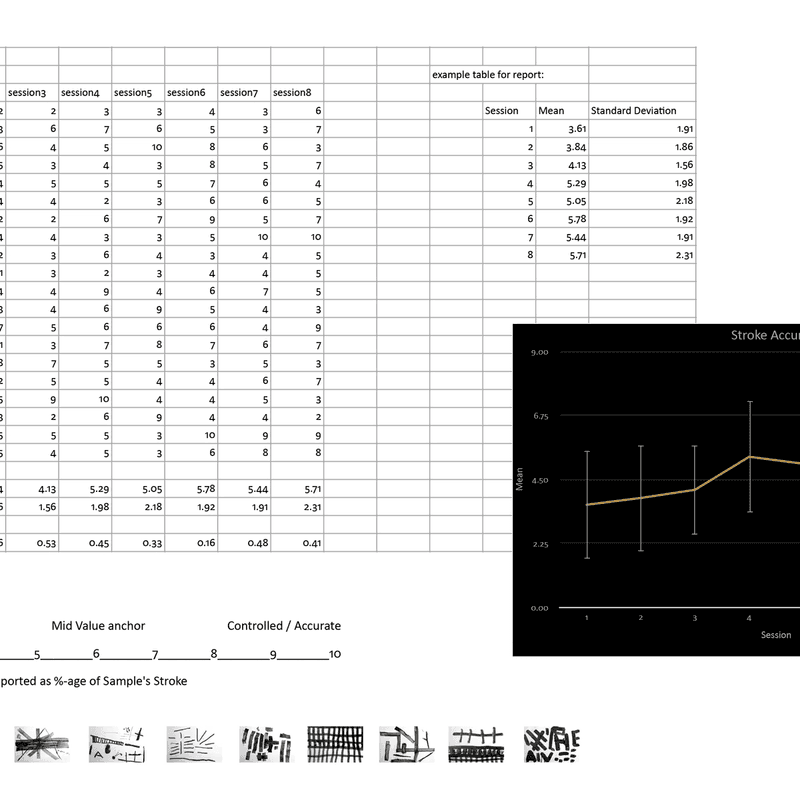

I had the pleasure to run the workshop in Texas in collaboration with Dr. Teri Evans-Palmer, Professor of Art Education. Together we outlined both research design and methodology (surveys & data collection methods) and we were able to record substantial data, which was processed with the help of Dr. Phillip Vaughan, Research Scientist.

A research paper on this exploration is ongoing.

Material: 11×17" semi-glossy paper, black tempera, balsa wood, sand paper.